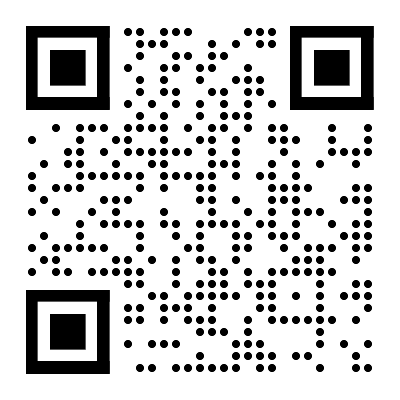

微信扫一扫联系客服

微信扫描二维码

进入报告厅H5

关注报告厅公众号

The term “sovereign wealth fund”—coined 15 years ago by the British economist Andrew Rozanov (2005)—denotes funds accumulated by a government that are invested, for many funds mostly abroad, to benefit the country in the future. The purpose of these funds has been to smooth out revenues from fossil fuels and other natural resources, supplement pension funds, promote development, and/or save for a rainy day. Estimates of the assets under management of sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) at the end of 2007 ranged from $2.6 trillion (Stone and Truman 2016) to $3.2 trillion (Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute in Stone and Truman 2016) to $4.0 trillion (Global SWF 2021).1 Analysts predicted that total SWF assets under management would increase to as much as $17.5 trillion by 2017 (Truman 2010). In the event, their total assets were much lower. The Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute estimate for the end of 2020 is $8.3 trillion, essentially the same figure used in this Policy Brief for the SWFs it covers.

SWFs have never been without controversy. In 2007, some analysts expressed concerns that these large pools of investible funds owned by governments, many of which were on the fringes of the global financial system, would be used for political purposes or that they could disturb the global financial system. The potentially distorting impact of SWFs on the economies of countries that owned them was also a source of concern, raising questions about their governance and possible politicization. Responding to these concerns, Truman (2007, 2008) developed a SWF scoreboard to assess the transparency and accountability of these funds and encourage funds to improve their public images.3

积分充值

30积分

6.00元

90积分

18.00元

150+8积分

30.00元

340+20积分

68.00元

640+50积分

128.00元

990+70积分

198.00元

1640+140积分

328.00元

微信支付

余额支付

积分充值

应付金额:

0 元

请登录,再发表你的看法

登录/注册